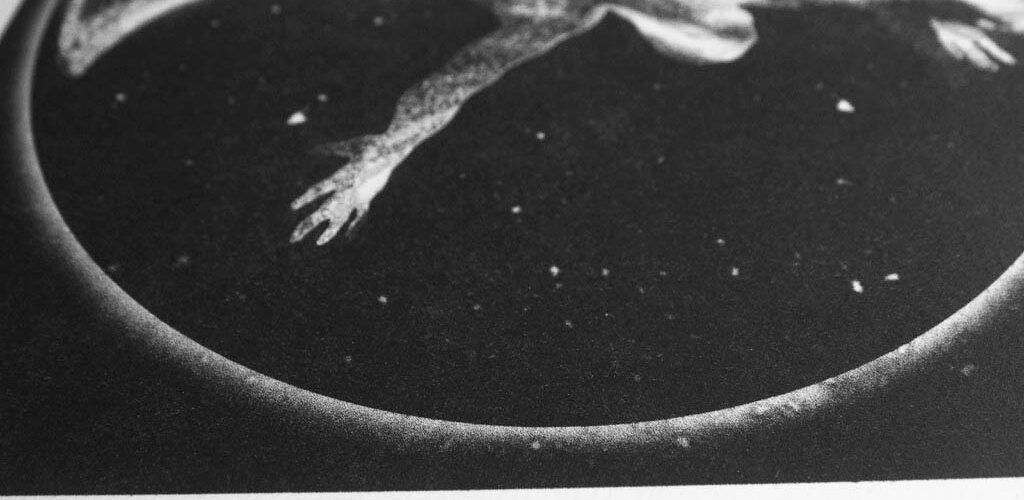

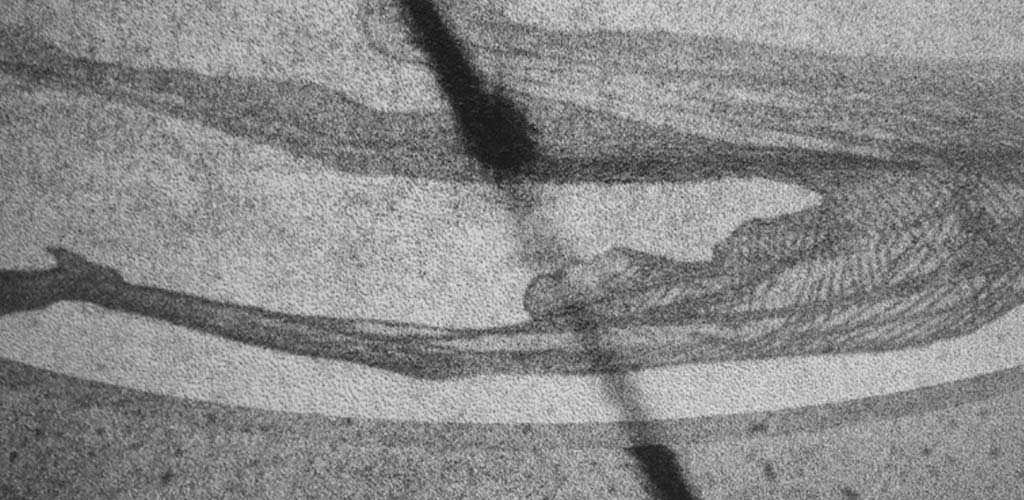

… In 2016 I was asked to contribute artwork to an exhibition celebrating the life and work of William Shakespeare. At the time I was working on a series of rather elaborate monochrome lithographs and somehow this request coupled with its opportunity for wordplay and theatricality had an immediate effect on my work. The Bard’s themes both energised and informed my ideas and the body of work grew very rapidly into a number of conceptual designs. Deciding to work on an art book was a logical and thrilling possibility of getting the body of work into the world. I have made artist’s books before and my professional life started in publishing – so taking this particular project into the realms of book-making felt like life turning full circle. “Out Brief Candle’s” central narrative encompasses the brevity and unexpected consequences of human life; creating an interplay between the Bard’s famed words and new unfamiliar imagery. I would like to invite the viewer to become an integral part of the experience, interpreting the work afresh, with the art book its stage. The visual language of the artwork draws inspiration from classic engravings and iconic black and white films of Tarkovsky and Bergman; re-imagining the images and the creative techniques though the prism of modern technology and the world around us.

So far 40 original plates have been created.

Original artist lithographs are printed by the artist in an edition 50 each. Image size: 25 x 25 cms, paper size 38 x 50 cms. Printed on Somerset 250gms cotton paper.

Individual prints are available to buy. Availability changes all the time as the works are printed by hand in small batches.

If you are interested, please contact Veta.

Update January 2023:

This year marks 400 years since the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio. Seven years after the bard’s death in 1616! Well, sometimes the wait is the only way…Ironically, I began working on the “Out Brief Candle” series around 2016, on Shakespeare’s 400 death anniversary and not long after I moved my studio from London to Stamford. Seven years, Brexit, pandemic, and lot of personal changes later, I am still going and feeling keen to share my work with the world like never before.

My work, still and quite simply, is an artist’s reimagining of ideas on life and its relentless pace and changes. That never gets old or boring. It is also, and always has been, an act of curiosity and wonder connecting the words of Shakespeare with modern sensibilities and technology.

I am now looking for opportunities to exhibit / collaborate further in 2023-24.

Whether it is showing the original artworks or enlarged digital prints (on paper or fabrics, flexible production) I would be delighted to explore all potential opportunities. Talks and workshops, possibly an animated projection in public areas are also something I wanted to consider.

I have worked on the series and exhibited the work over the past challenging years (the Royal Academy, Shakespeare’s Globe and a solo show with Eames Fine Art being a few venues of note).

My ambition is to reflect and explore with the viewers their own “Inner theatre of meditation” (borrowing the words of venerable Ted Hughes here). The themes placed centre stage are of internal conflicts and complexities of our environments. The aim is to learn “to know thyself”. This work has been a quest for me to make sense of one’s own awareness, the pulls and twists of order and chaos, and perceptions of change.

I am looking forward to continuing on this journey. VETA

Out Brief Candle - Publication

"Out Brief Candle", Eames Fine Art Printroom, London. February - April 2020

"Out Brief Candle" in RA Summer Show

Q&A

– 1. How did the “Out Brief Candle” series begin? –

Fair to say it was a bit of an accident. There were two events in the spring of 2016 that started it all off.

The first one was that I hurt my back. We were moving out of London to a new home and printmaking studio. I was busy converting an old neglected barn to create my new space to work. This was exciting but required a lot of hard physical work and was not without doubts regarding the sanity of what we were attempting to reshape in our life. Cut down with back pain, I spent over a month in bed. Working at the press was out of the question.

And this is where the next coincidence came to materialize. I had an impending deadline to submit artwork for a group exhibition at the Globe Theatre dedicated to a big Shakespeare’s anniversary that year. I could have said no to the opportunity or settled on reworking some old images, but I did not. And looking back, I think this provided the trigger to attempt something outside my comfort zone, reassess my routines and reconnect with meaningful things in life. Now, I love printmaking. Its material and physical limits as well as some open-ended possibilities work for me like nothing else. I love my press and I love my messy oily inks, but having found myself unable to continue with certain physical routines I felt I had to take the chance to re-examine how and why I was making my artwork and incorporating some of my skills as a digital designer felt like a sensible option.

I did not have much of a plan. But I had time. I delved into books and returned to what was accessible and what I knew well – digital image-making. This enforced physical pause turned out to be an opportunity to look at a new way of working for me. Referencing the work to Shakespeare provided a much-needed connection with the outside world. But the real aim for me was not to meet a deadline, but rather to look inwards, to find a sustainable pattern for my practice and engagement with important subjects I felt ready to tackle.

– 2. So why Shakespeare? –

I tend to be drawn to both appreciating and making work that would revel in thought exchanges and different (sometimes opposing) viewpoints; an ambiguous / open-ended kind.

For me, this is the most fascinating trick in art. Weaving together silences and gaps, what is said and what is unsaid, asking rather than answering questions. This is what makes it, for me, genuinely exciting and truly worthwhile.

The world reflects differently in each and every human’s mind. And the best art is equally completed and challenged by an input from its audience. There is no objectivity. The creator is not a god-like figure. Life is a flux between chaos and logic. But through art one can and does, have a chance to experience the world from another person’s point of view and learn how to fill those gaps, join the dots, stay alert and engaged and beyond that; put an unconditional value on the beauty and brevity of life.

In Shakespeare’s texts then, a human mind finds whatever it wants to find or open to discover. There are ample gaps to fill, conclusions to draw, parallels to trace, alternatives to consider. The genius seems to be in the works’ glue-like quality to create chains of human interaction and thought. A true ability to connect. And naturally with Shakespeare, I stumbled upon an incredible sparring partner. The more I read and listened – the more I wanted to think about it, argue and contend. Just think of the images words like this could invoke: no blemish but the mind, quality of mercy, gap of time, the edge of all extremity, skipping spirt and so on…

– 3. Concepts –

Early on I decided a couple of things. Firstly, I needed some formal uniformity to the series. Secondly, I would not be able to stop at just a couple of images.

I was keen to explore the language, the associations, the concepts. And because there was so much original poetic wealth to work with and my imagination was already suitably engaged with a number of different subjects, I had to figure out a stable and coherent framework and discipline to accommodate all that variation. I am not an expert here, but I think I picked on some echoes from key theatrical concepts: those of form, light, perception and motion. Things that make theatre resonate so strongly with a human mind. There was additionally a fifth silent device – namely the subject itself. Time.

First, I settled on the square format. A square is a directionally stable form. It allows for all sorts of internal movements without risking or influencing integrity. Also, a square’s boundary will manifest the limits of time itself. A human lifeline is finite – the best we can try is to make the most of it. As my imagination continued to contemplate the poetry, I started to consider the images that would fill the squares. I knew it would be a set of physically improbable images verging on material deception and inaccuracy. I wanted to convey the excitement of imagination that I experienced and the best way I thought would be in return to provoke the excitement in the viewer. As a printmaker I was used to making flat two-dimensional works. But never before I needed to work out a method in which the depth of the space I would work in would become critical to the whole visual language. This is where I completely stepped outside my comfort zone.

Very quickly I came to realise that depth requires light. Avoiding it would make my efforts lifeless and a mere illustration. The sense of vision paired with memory elevates the way humans perceive light to almost metaphorical heights. Light can be both beautiful and troubling, too much/too little send different signals to human imagination. It defines the shapes and its lack informs the deepest of depths. Reduced to its monochromatic bareness is a dramatic tool to express a very wide range of emotions and situations within the human condition. Shaping my images with light would become a central part of the series identity.

I am also frequently told that the work reminds people of the early black and white photography and cinema. This is not a coincidence. It is both a creative choice and a technical means of production. Mixing photography and drawing and then converting collaged and edited images into film transparencies as part of the process lends to paradoxical perception. The physical qualities are both real and unreal, consistent enough with material laws for the eye to consider the composition probable. Yet curious enough to stress the mind into alertness and engagement.

The things and bodies that interest me are all moving objects. And the moving world is impossible to avoid when narrating about human condition. We think through movement more often then we acknowledge. Movement relates to fundamental human concepts: near – far; hard – soft; weak – strong; open – closed etc. Most of our material concepts are rooted in animate movements, both those observed and the ones we make ourselves. Exploring the world through our bodies and movement is what we do. Learning how to move is the first thing a human being does. Thereafter a human learns by observing motion of other objects outside her own body. Movement starts chaotic and clumsy and progresses to seamless and logical, then the process tends to reverse. I like to imagine the images as frames from an animation reel. This is something I entertain myself with when putting together a composition. I might give elements a slight tilt or unbalance parts so as to hint that the viewer observes an open-ended event. For me it is akin to freezing a basic unit of memory in a single frame.

– 4. Digital Traditional Artwork –

To paraphrase Shakespeare, art holds a mirror up to nature and depending on the state of the said nature an artist is naturally expected to use appropriate tools to create appropriate mirrors.

Ultimately it is what you do to a viewer and not how you do it that matters. Saying that, art always looks for new ways to reach out to its audience. Now, as artists we aim to affect human senses. But the ways of how humans perceive and engage with their senses are influenced and perpetually changed evolving realities.

Today’s reality then has complexities that are multilinear and fragmented and tangled. And present and even future generations would want to understand them as such. They would also want to know how we reacted and endured the changes that our lifetime afforded us. The main one, of course, being the technological spell we are under. It is not a revelation that humans at the turn of this century came to express and perceive a lot of our experiences through technology.

And so, it was my return to digital image manipulation that energized me and gave me confidence that the project like this could be pulled off. I just had a feeling that to incorporate a vast number of sometimes contradictory subjects I had to mix together both “traditional” (physical making techniques that I came to love and practice) and “modern” methods of manipulating images and, hence thinking. Shakespeare himself spoke of “corrupting” words – I think of it as corrupting images. In the name of an idea and art of course.

To better relate to contemporary sensibilities, I naturally needed to have a go at contemporary visual language. To embrace in my work elements of fabricated, artificial stuff: mechanical precision, repetition and cloning, ultimately an algorithm based geometry.

To construct my compositions I move between two distinct visual vocabularies: freehand drawing (expressive and lucid and organic and free-flowing) and mechanical elements designed by algorithms and let them interact. I think of it as a paradox of a human reality being somewhere halfway between nature and technology. The same paradox exists in my studio where the digital part of the process is firmly sandwiched by analogue, physical methods of making. I draw by hand on paper, plate or now on Ipad. Then digitally assemble and manipulate drawings and photos. But at the end I create physical artefacts, the print itself. And that is supremely important to me.

In the end, there must be something not just to see but to interact with on a corporeal level: something that reflects the light, something to touch, something immediate to connect with.

There are several avenues open to a printmaker with regards to translating a digitally assembled image to print: there is of course silkscreen and photoetching, but I made my choice from the start on using industrial positive lithographical plates. They provide the richest definition and are the most sensitive ones to the level of monochromatic tone and linear precision I was after. The plates are fiddly in a rudimentary art studio set-up as their performance is better suited for a strictly controlled industrial process.

There is yet another paradox. The plates I use are on the way out. Quite literally they will be phased out of production in a matter of years. At least I hope years, could be less. As the printing industry methods are rapidly changing in favour of direct printing from files the plates will disappear from circulation very soon. So, by choosing to use them I was deliberate from the start in narrowing my time to complete the project. And also giving it a unique time-stamp. As my statement as to when in time the work was made. Another quirk of my process is that I choose to print on my intaglio press. This again brings together technologies that are not meant for each other. I like to think that I force them into co-existing because I have the reason for that, it is a mind over matter scenario which took some time to work out how to perfect with a lot of trial and error.

A lot of what a printmaker does depends on material qualities of the matter we work with and how it is manipulated. A great deal of the outcomes is unpredictable. The results I came to like are of a great range of tone and texture of my recent prints. The images can feel either weightless and bright or dense with almost mezzotint quality depth. And everything in between. And I adore this range, variety and precision. The variable nature of the printmaking process is what makes it captivating in my opinion. It ultimately lends itself to the endless reinvention.

The chances are that I am not going to stop making my “Out Brief Candle” prints in the foreseeable future. I have marked two dozen more wordplays that engage me in thinking images and I am sure many more will call for attention later. Once dreamt an artist makes, or as Shakespeare said “thinking makes it so”.

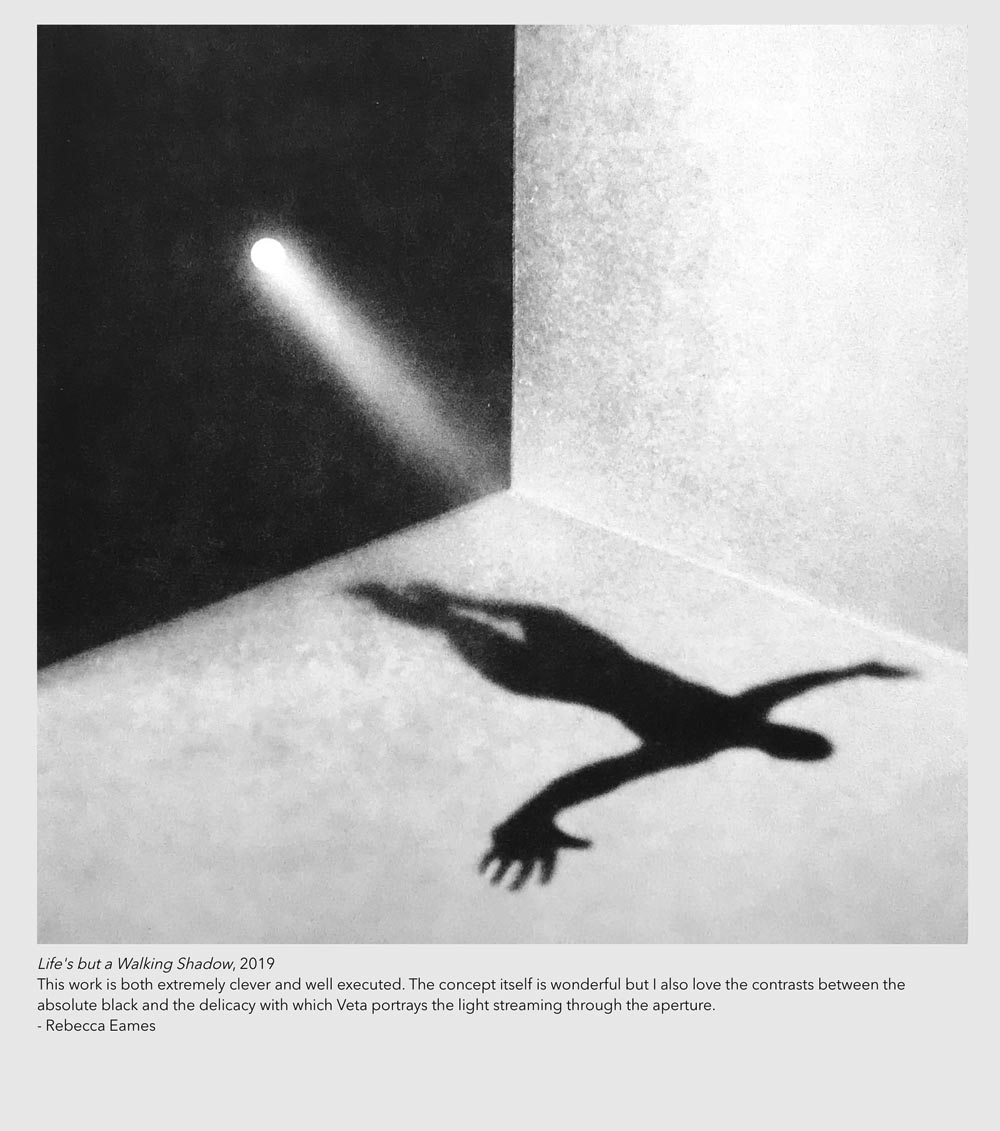

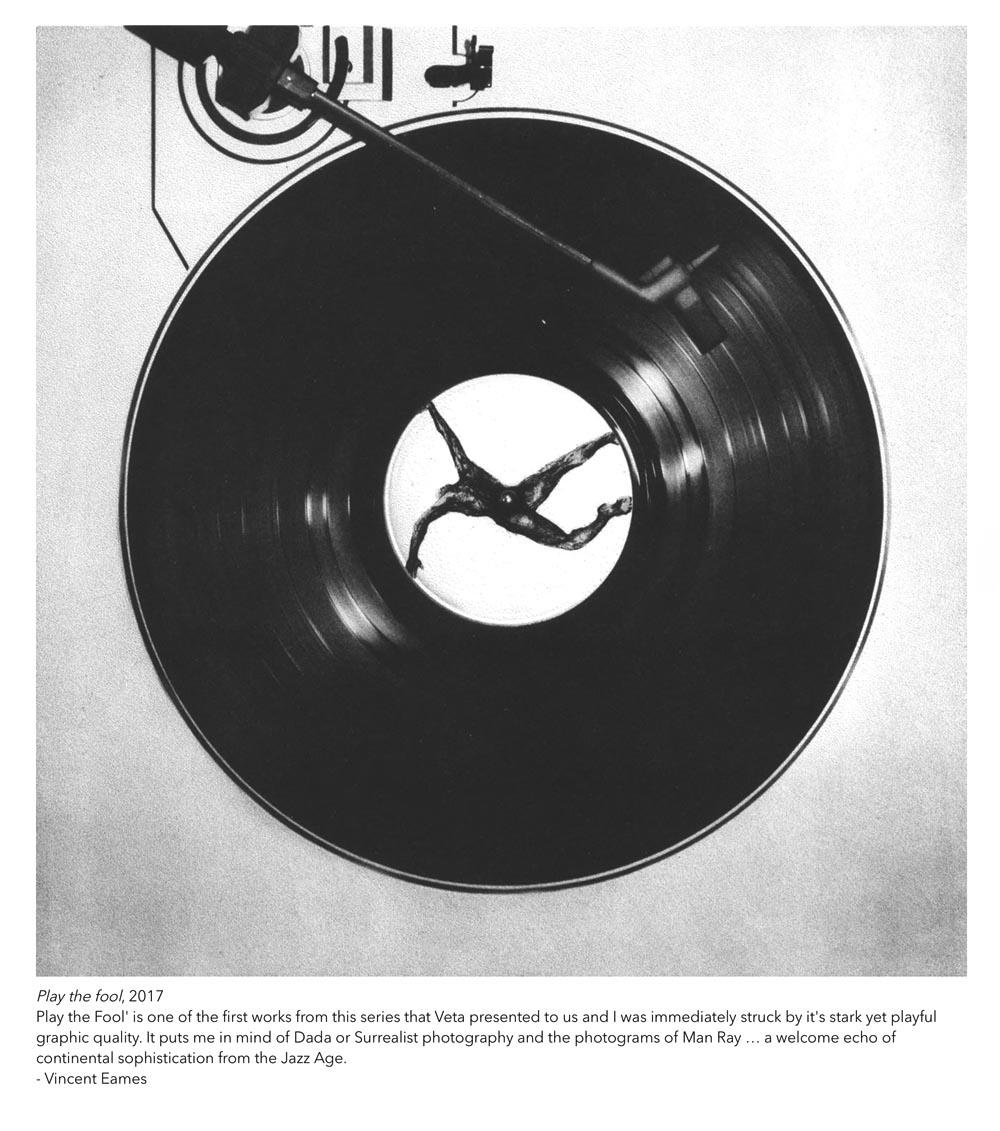

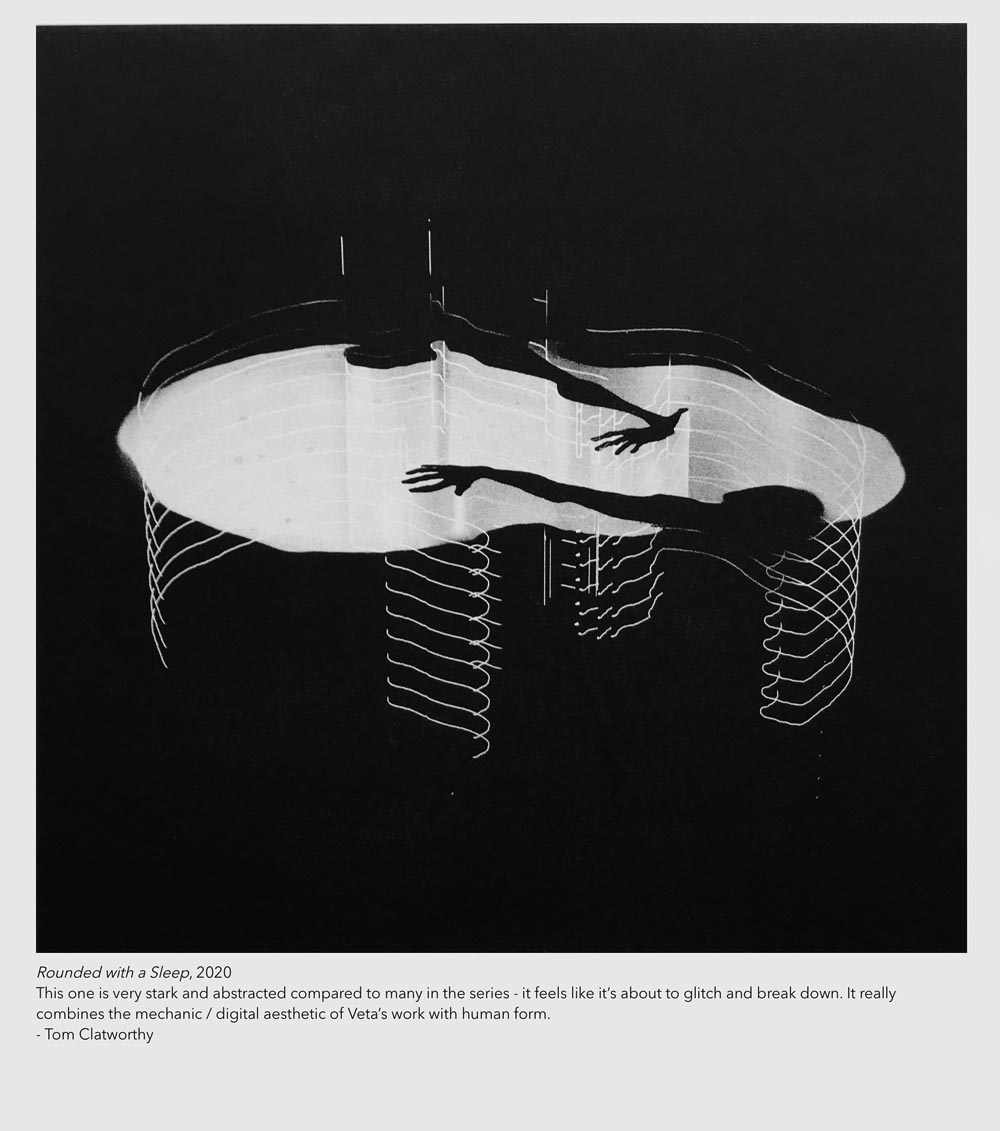

Reflections on Out Brief Candle